EMPIRES FALL | THE DANCE GOES ON

MATTHEW TIERNEY

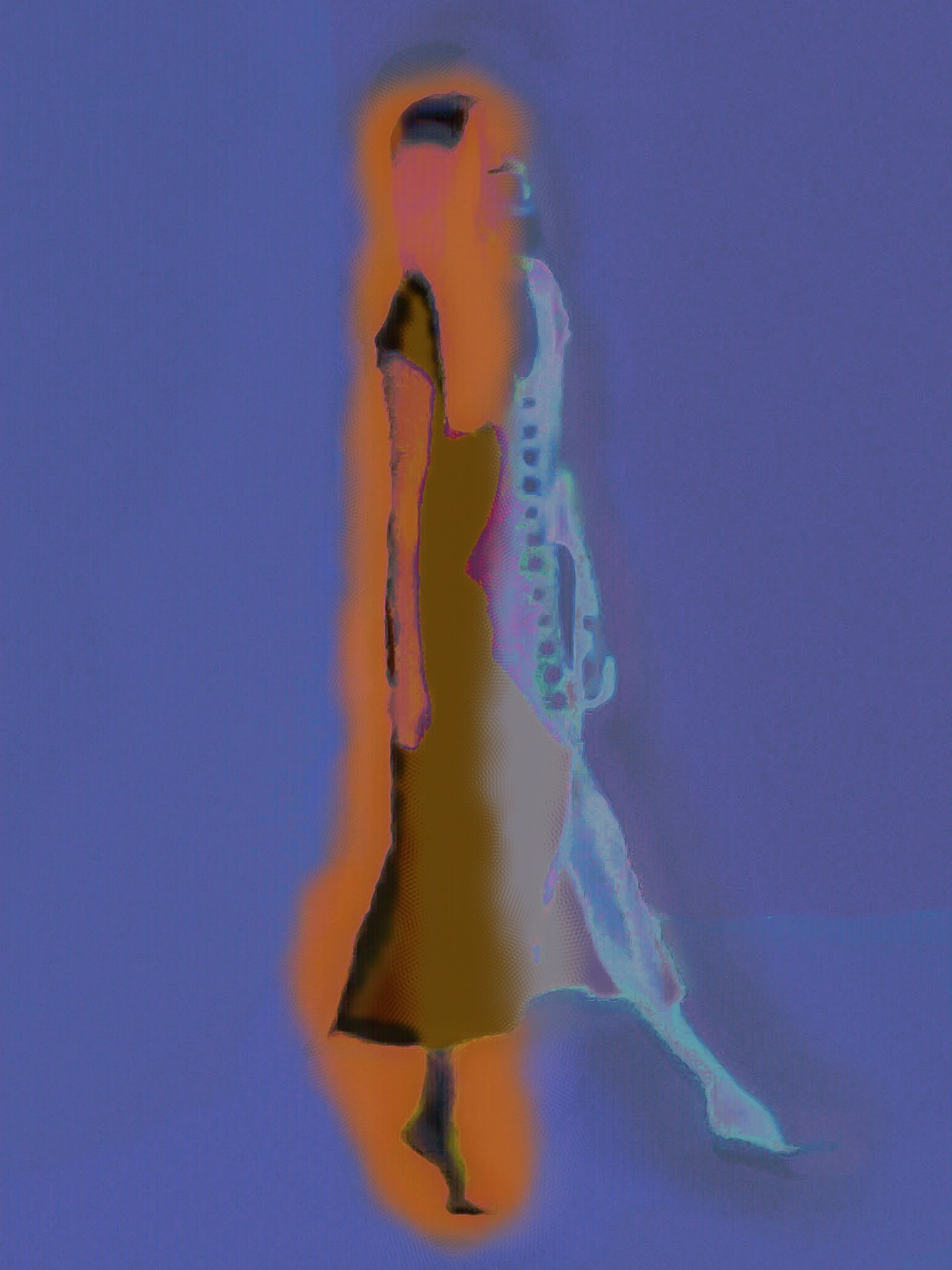

Matthew Tierney is a young Silicon Valley-born, New York-based painter pushing the possibilities of painting in the digital age. His new show, empires fall | the dance goes on centers on the Dancers, a bold series of sixteen large multicolored ink-on-canvas paintings that blur the line between the digital and analog, between painter and screen.

With each Dancer, Tierney is dancing with the process of painting itself. He is dancing with his subject, and he is dancing with her absence. He dances with painting, and he dances with the absence of painting. He choreographs an intimate history of the very possibilities of his own artistry in a digital age.

Upon seeing Tierney’s Dancers, the painter David Hockney remarked, “Perspective is a frozen moment. That’s what you’re shattering”. Perhaps Hockney was thinking of perspective in the way that Pavel Florensky, the Russian polymath and art historian, thinks of traditional perspective as being shattered in Byzantine icons. Florensky defines what he calls the “polycentredness” of icons, that are “deviations from the laws of linear perspective”.

Tierney is just such a deviant. And in today's contemporary art scene, Tierney is a deviation himself. He stands within in his work. Byzantine icons are perhaps the best way to approach him. He gives us a 21st Century icon, an illuminated portrait of a divine figure meant for worship, awe, fear—holy transcendence. And she is as much an icon as she is a testament to the possibility of making a digital icon.

Art historian Bissera Pentcheva defines Byzantine icons as performative: “The icon performed through its materiality… in a process of becoming, changing, and performing before the faithful”. The materiality was created through imprinting, seals intaglios, wax: “The Byzantine icon is a surface that has received the imprint of divine form”. Tierney too manifests his divine form by printing, imprinting, repetition. While the exact nature of Tierney’s process is unknown, we do know that it takes place across every-size screen, paper, canvas.

Though tablets, phones, computers play their role, equally present and active is the brush, the pen, the camera, the hand. This confoundingly endless process goes between human and machine, back and forth, rinse, repeat ad nauseum between the real and digital, printing and reprinting each iteration. This complex conversation between paint, pixel, and everything in between is the story of an artist desperately trying to retain his grasp on an image, screened by glass, and garner beauty from loss through transfer. The result is not a print or edition: the Dancers, each a unique, are paintings. Outside time, they live in canvas.

Tierney’s work becomes an archive of human and digital processes. An archive in the manner in which Jacques Derrida defines it: an archive that “destroys in advance its own archive”. Though each dancer is individually an archive of the infinite layering of each image, there is loss with each reprinting, and the record of this history is destroyed by its layering. We have no catalogue of the transferences that occurred, we only know they occurred and that we stand in front of them.

Perhaps Tierney’s dancer is a record of eras bygone. The French Empire is gone, but the dancers in the Louvre dance on. Only now, mostly in the gift shop, or on camera phones. Tierney’s dancer looks as though it might have started with a Degas, but was cast into bronze, then re-cast, re-painted, copyrighted, sold, factory-made, museum gift-shopped, photographed, postcarded, hawked outside The Met, dropped in the rain, mailed, photographed, posted, blogged, retagged, filtered, forgotten. But Tierney remembers, and rescues the elemental beauty in the rubble.

Viewed together, the Dancers unify into an overwhelming vision. They move, they step, they breathe together. Their endless layering creates a supernatural harmonious cacophony.

In Tierney’s world, we are visitors from another planet, arriving to earth after the apocalypse, and no longer know how to play MPEGs, and we no longer have the codices to make move all the useless images stillborn in our pockets. A pantheon of the broken GIF.

In the intimate back room of empires fall, we find a different perspective of Tierney’s post-apocalypse. A world left curated, as if the fires were still alight in the caves of Lasceaux. The hand-painted text-paintings on canvas, one or two-word wordplays, are pregnant epitaphs for Civilization itself.

And yet, the dance goes on: the dancers dance on in these caves in other forms, their own ghosts and shadows. Tierney triumphs in the rubble. The dancers are quite simply: unavoidably beautiful. They walk like Fassbinder’s Maria Braun amidst a bombed-out Berlin, but in high heels and a fur coat, smoking a cigarette. They are bathed in the angelic light Gustave Moreau shines on Salome.

What then of us? Who are we when we walk the hall of dancers? Are we emperors? Choreographers? Are we dancers, too? Or mere tourists? Does the dancer take our hand? Where’s the orchestra? One thing is certain: Matthew Tierney has some beautiful thoughts on the subject.

— Harley Adams —